Published 2014

Single 7 part poem

Illumination by Clarence Wolfshohl

$15.00

First Poet Laureate of Missouri

Bilingual Edition German/English

LILIOM Verlag, 2012

$20.00 (Cover illustration by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

Poet as Grand Marshal of the Fall Parade

Doubting the gravitas, the decorum, it’s poetry after all,

and being led by a Boy Scout honor guard that’s following a police car’s

flashing lights, their brown shirts sashed with merit badges,

and behind them the poet bucket-seated in a low-riding wine-dark sports car.

From a small bag, he tosses candy to children who are wondering

why they’re not watching Saturday morning cartoons, knowing Halloween

is a month off. Standing with their plastic Wal-Mart and Moser bags,

costumed in sleep they wake to the brash high school marching band

as it gracelessly plays what is half-remembered after so few weeks of practice

this early in the school year. The cough and clatter of two diesel tractors,

a wagon pulled by mules, another by horses, the women’s garden club

armed with rakes and shovels, the women’s Red Hat Society, a rabble

from the Chamber of Commerce, the mayor biking in circles

around the too slow procession, and whatever else joins in..

The poet agreed thinking this is what football players are adored into doing,

but he’s never led a team to victory much less played, and he considered wearing

shoulder pads outside his suit with poems scrawled in inch-high letters on

the plastic, but he was afraid to confuse the mile-long, one-person-deep crowd

more than they already were as he passed out poems once the candy ran out.

Bogged Down

At first the body was thought to be the missing boy from last year,

lost on a class trip

along the Baltic Sea; then it was the man who left the Danish bar one hour

before New Year’s fireworks

and hasn’t been seen in a decade; or the wife, forty years

since she walked out

of the grocery store, there’s that little left. Perhaps it’s all of them returning

to tell

their secrets in this one body, but there’s something odd about the throat,

slashed ear

to ear, rope burns, cracked skull, head half shaved, blindfolded, feet broken,

legs lacerated,

left arm severed, chest wound, and staked down, yet resting peacefully,

face beatific, each wound sacred.

Preserved peat-perfect: forehead smooth, skin relaxed, one side of the face

flattened from

an interminable sleep, stubble on the chin, knees folded fetally, missing

for two millennia

and no one missing. Waterlogged, acidic tannins turning skin to leather,

fine enough

for police finger printing, though the crime will never be known. Tacitus records

that in Germania,

98 A.D., The coward, the unwarlike, the man stained with abominable vices, is plunged

into the mire or the morass.

Or for other reasons . . . purified in a secret lake, slaves perform the rite,

who are instantly swallowed up by its waters.

The sacrificed, the executed, resurfacing with us, who day by day wonder the way

and wander the difference.

New & Selected Poems

BkMk Press-UMKC 2009

$16.00 (Cover and inside art by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

The Paseo

-for Federico Garcia Lorca

The last flung-back, bullet struck

moment on an arid Andalusian slope

of the Spanish Civil War;

a soldier’s death caught

in shades of black and white,

his body halfway falling back forever

toward his shadow, his rifle pointed

at heaven, his head turned away,

already forgetting to tell us the way.

A woman’s gaunt upturned face,

lips drawn back from her teeth, a forehead

of plowed wrinkles, her eyes straining

to find the sewing-machine hidden

in the sky, clouds being stitched

together with threads of fear,

and we know what happened,

the dusty, dive-bombed rubble

of Barcelona, the child at the slope

of her exposed breast

nursing on oblivion.

In the city where I lived one summer

oaks rose in civil explosions of leaves.

Branches arbored the boulevards

over the speeding cars and trucks

that had somewhere more important

in mind, work or love, not the quaking

heart of an air raid siren.

Mostly it was Friday,

maybe Saturday evenings, that I drove

the Paseo as it was called, the body of asphalt

releasing the day’s mesmerizing heat.

Along the way, fountains reared horses

and breached dolphins, spouting a moist

eternal glitter, surrounded by groomed

green esplanades where I might stroll

an equally endless time. In one

breath paseo simply means ride,

and in a different one it means

take him for a ride, the end of one

language and the beginning of another.

House of Turtle

I can’t tell you where to start, maybe I don’t know,

or maybe I’m simply not ready for the responsibility,

though it has nothing to do with not wanting to help,

nothing to do with all the possible guilts that sweep

over us for not having loved enough, or been present

enough, or even not having stopped the car and moved

the turtle off the road, and finding the flattened mess

when we returned, having watched in the rearview

mirror another driver intentionally swerve. We must

take into account another time it was hopeless,

of just pointless, when we had not yet surrendered

hope, when the pond by the highway was drained

for a new apartment complex, the backhoe with its

claw sunk for the night into the breached embankment,

waiting for morning to again swallow another mouthful

of earth and spit it out. What more could be done,

the quitting-time traffic no longer able to dodge

those orphaned by the air, who crawled for other waters,

and over the asphalt the hundred or so moss-backed

shells were cracked and savaged flat. Perhaps this is

just a warning, like the children standing in a down-

pour shouting over whether running or walking

through the rain will leave them drier, even as the rain

falls harder, drenching their most refined arguments.

Prose Poem

WordTech Communications, 2008

$17.00 (Cover illustration by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

Blue Migration

Jake’s in some kind of too late mid-life crisis, not that he thinks in those terms, though he’s consumed by a feeling of unease, really a subtle and growing disease, whose diagnosis is not obvious to any of his friends, or health care workers, two types he’s strenuously avoided these last months. It could quickly turn deadly, not that there was really any hopeful prognosis, and too easily, cynically, summed up behind his back by “sooner or later.”

He turns into the satellite bank’s parking lot, the afternoon a perfection of blue?there’s nothing to see with his head tilted back into a falling-up sky. On days like this, emergency rooms are crowded with a rush of vertigo cases: sand grains blown off the beaches of patients’ inner ears, all who want to leave the planet, be transported, seduced into the infinite, eternal, ethereal, out-of-body, out-of-mind, out-of-this-stinking-place, head-for-the-hills, head-for-the-stars, take-the-money-and-run . . . wait he’s stopped, the only dented, wheel-well rusted, right rear-taillight-missing, no hub caps, car in the lot, that looks half like an abandoned osprey nest. When he opens the door, he’s taking flight, moving out onto a limb of sidewalk, and he almost raises his arms to begin flapping.

Jake enters through the double-tinted glass doors, hands in his pockets, there to check his balance, walk the tightrope of accounting, slip past the noose of overdrafts, make a small deposit. The silent TV mounted in one ceiling corner displays the enclosed captions of CNN, morning’s stale coffee sits in a silver urn beside the stacked peak of Styrofoam cups. A bowl of Jolly Rogers by the only open teller’s window, and in her practiced, mellifluous voice she says, “How can I help you?” and he can’t remember, he’s a fledgling falling from a nest, a jettisoned rocket booster tumbling through space, an aging man in a too quickly aging moment.

She asks again, and rather than opening his wallet and signing the check, he says in a meek monotone, “Give me all your money,” and pulling off his sweat-stained baseball cap to use as a pathetic receptacle, the teller dutifully, awkwardly stuffs the hat and hands it back. He flies out as slowly as he walked in. He’s sitting in the car, staring up through the dirty windshield at a single stringy cloud that’s cracked the sky, when three police cars careen past, lights flashing. They run into the bank, guns drawn.

Having completed their reports, dusted for fingerprints, reviewed the video cameras, they have no leads. Jake’s still nesting in his car when the police leave the bank. It’s not clear to him, the money spilled across the passenger seat, wrapped in small bundles like green dominoes, if he’s dead or just the soul of a bird in flight.

How Tables Learn to Talk

Jake can tell you what and maybe why he pulled back the covers and got up, sitting for a moment on the edge of the bed, taking one conscious breath then another, inflating the body back to life, left hand feeling for glasses on the night stand, chin on chest keeping his head from falling to the floor.

It was around 2 a.m. when the table startled itself awake, realizing it was no longer in the kitchen and hadn’t been for hours. With wooden legs and a lumbering Frankenstein gait, it must have sleepwalked into the living room. Paralyzed with fear, it couldn’t make it back to surround itself with chairs and so became a ventriloquist, shouting through the woman standing next to it, Stella in a night shirt and naked from the waist down.

It must be moved now, not before breakfast, not after showering, not before leaving for work, but now in the moonlight slipping across the newly waxed floor, dry with shadows. Tables are so hysterical when they wake in the wrong room.

Reviews:

Timberline, 2007

$12.00 (Cover Photo by Alan Berner)

Selections:

Ice Bound

Sky’s gray sheet spreads icy rain.

Through the night we heard the branches cracking.

Now they bend with the bowed ache of apostrophes.

Backs to the window, sitting on the couch, we listen

as the radio announces the list of schools closed.

An hour earlier I inched my way along

the road, tires spinning toward the ditch.

Now I read aloud to a teenage daughter,

who tolerates my foolishness, my claim

that Lao Tzu traversed a more slippery world.

With two books open on my lap, one in my hand,

two on the floor, I’m surrounded by imperfect

translations : a gathering chaos; something

mysteriously formed; without beginning,

without end; formless and perfect .

She responds, Sure,

I knew that , so what ? I persist:

that existed before the heavens and the earth;

before the universe was born . She’s ready to go

upstairs and listen to the radio. I ask,

What was her face before her parents were born ?

she answers, Nothing . I ask again.

She says it again. Where are the angels,

nights on humble knees, the psalms of faith,

the saints of daylight? S he walks out of the room.

I’m surrounded by thin books.

How pointless to go anywhere on this day,

or maybe any other, but then

the time comes when there is

no other way but to stand firm on ice.

Manifest Breakfast

In a house buttressed by books and slanted morning light

slicing across the grain of the kitchen table, Lieutenant Colonel

George Armstrong Custer’s 1876 orders to pursue the Sioux,

Cheyenne , Sans Arcs, Blackfeet , sits beside an emptied bowl

of Grape Nuts. The document is randomly punctuated with crumbs

from half-burnt toast, difficult to read the general’s elegantly looping

Nineteenth Century signature and the limits of force given Custer’s command.

My wife has printed over in her typewriter-meticulous style a grocery list

of olive oil, cilantro, garlic, tortellini, supplies for this evening’s company,

but not the 7 th Cavalry last seen surrounded near the banks of the Little Big Horn.

There’s also a lengthy paragraph to herself , notes on rehabbing

the upstairs bathroom and the rest of her destiny. She’s scribbled

calculations , an attempt at reviving a diminishing bank account,

and an addendum to the Christmas card list, and it’s only February.

This morning my wife sits down to rewrite Custer’s orders to pursue the Sioux.

WordTech Communications, 2006

$17.00 (Cover illustration by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

Civilized Sacrifice

I have climbed the backs of gods too. It’s not so

strange, dressed in heavy coat and boots, hat

pulled down to the eyebrows, cheeks windburnt,

gloved fingers numb, and each brief breath prayed

upon, each step thrown onto the loose altar of stone.

Blinded by spires of light, I’ve looked away

as the unblemished blue splintered in all directions.

And I’ve backed away from the sheer

precipice, the infinite suddenly a fearful measure,

the way down to tundra and the jagged maze of

granite, leaving only a crevice in which to cower.

I’ve lain on the steep slopes of night under spruce,

wrapped against rain and cold, and watched clouds

explode in my face. Stark boughs reached

then sagged back in a sweeping, resolute silence.

I was shaken loose by thunder and lightning,

like the small girl, named Juanita by strangers.

She tumbled a hundred yards down

Nevado Ampato peak, her whereabouts unquestioned

for five hundred years until a nearby volcano

began a festering eruption, thawing the slope,

and wrapped in her illiclia shawl woven in the ancient

Cuzco tradition, wearing a toucan- and parrot-feathered

headdress, her frozen fetal posture a last effort

at warmth above tree line amid ice fields, there

to address and redress for rain and maize, for

full vats of fermenting beer, plentiful llama herds,

for the civilized sacrifice, to be buried alive and wait

in private, as we all do to speak with our gods, hoping

to appease, to know, to secure the illusive cosmic

machinery, and in that last numb moment her left

hand gripped her dress for the intervening centuries.

Minor Gods

Another roadside bomb, another suicide

bomber, another dozen blind-folded, hands-tied-

behind-the-back bodies found half buried at the town dump,

it’s how a Saturday explodes until I turn off

the radio and look out the east window at a tabby

crouched in explosive morning light and acting strangely.

I hurry outside to rescue an eight-inch long, pencil-thin,

ring-neck snake before it is playfully eviscerated.

A hundred yards into the woods, the palm heat

of cupped hands has pacified its coiled panic

and I scold it to be more careful before it calmly

slithers into a brush pile and into another ambush.

Balanced between two flood lights on the west wall,

phoebes again build a nest out of moss and spittle,

and I build a four-feet high fence on the ground below them.

They quickly abandon their efforts as if not understanding

what I’m trying to keep out and keep in. Occasionally,

I see their bobbing drab-gray tails on a nearby branch.

I leave the fence standing. I blame the cats

without evidence of guilt. Weeks later,

the phoebes return, the same pair or different,

I don’t know after so many seasons of failed attempts

on every wall of the house, including the black snake

that scaled ten feet of siding to eat the hatchlings.

From the kitchen window, I watch them fly back

and forth through the gauntlet of clawed hunger,

too early to know ends except this flying.

Either the gods are omnipotent and not good,

according to Epicurus, just look at this world, or they are

good and not omnipotent, look at these phoebes.

Reviews:

Remedies for Vertigo

Walter Bargen

Cherry Grove Collections

ISBN Number: 1-933456-40-X

Reviewer: James Owens

Books go in search of their right readers, and Walter Bargen’s poems are looking for readers who understand the need of giving them the time and space to deploy their often oblique verbal machinery. Bargen’s poems usually seem plainspoken on first reading, straightforward narratives of working life, reflections on history or encounters with animals, mostly birds, that verge towards an uneasy recognition of the danger inherent simply in being alive. The poems, however, open up to deeper associations and subtleties on second and third readings.

The first poem in the book, “Playing Chicken,” from a sequence titled “Experiments in Flight,” serves as a sort of half-ironic ars poetica , though ostensibly an anecdote about a farm boy sent to catch a chicken for dinner and forced to approach the wary bird slantwise, as Emily Dickinson says one should stalk the truth of a poem.

He must act

as if he were headed in another direction,

and only coincidentally walking past

toward the shed for a shovel or to the storm cellar

for potatoes, all the time edging ever-so-slightly

sideways while staring straight ahead, but really

watching from the corner of his eye, then springing

and bending in one scooping motion into his arms,

a squawking, flapping chicken….

By the time a reader gets to the sixth and last poem in this opening sequence, it is clear that Bargen is thinking about more than the roundabout ways of slipping up on a poem. In “Flying on Instruments,” a man tries to rescue a trapped bird that misunderstands his kind intent and attempts to escape through a “shed’s cobwebbed window, leaving dusk/ streaked with dust and stars.” In a clear echo of the earlier poem, the man approaches the bird and “fails/ at rescue before grabbing it with one hand/ rather than scooping with two.” The man carries the caught bird to the shed’s door for release into the night and is

surprised

by its weight, or lack of weight, and feels

uncertain how tight to hold a handful of air.

He steps from the door into the dark

and he almost doesn’t notice his empty hands.

Bargen is not a poet who resorts to the easy moral, but this “door into the dark” and the man surprised by his “empty hands” surely suggests something about the ambivalence of weighing action and the significance of action against the world’s tendencies towards destruction and chaos, especially as a reader moving through Remedies for Vertigo encounters other “fail[ures]/ to rescue.” People in these poems try to save baby birds from cats, small snakes and nesting phoebes from cats, bumblebees from a glass jar, a cat from cold weather and a fallen tree. The best these attempts can do is to succeed temporarily. An “eight-inch-long, pencil-thin/ ring-neck snake,” rescued just before it is “playfully eviscerated” by a cat, “slithers into a brush pile and into another ambush” (“Minor Gods”).

In the human world, people often seem in need of rescue that never comes. “Civilized Sacrifice” moves from the attraction of climbing mountains—”I have climbed the backs of gods”—to a portrait of an Inca girl found naturally mummified in the Andes, five hundred years after she tumbled down a rocky slope to wait

in private, as we all do to speak with our gods, hoping

to appease, to know, to secure the illusive cosmic

machinery, and in that last numb moment her left

hand gripped her dress for the intervening centuries.

“Photographing the Wind” brings the potential rescuer’s powerlessness in the face of human tragedy into the contemporary world in a particularly harrowing way. The poem starts calmly, far from disaster, “sitting on the porch” and enjoying “a wholly comfortable wind,/ tailored and too expensive for the end/ of a ragged century,” but the century’s dynamics of danger and damage intrude on this peaceful scene in the form of a photograph of an African child dying in a famine, while a vulture waits nearby for a meal. Photographs, to borrow from Susan Sontag, are problematic, implicating the viewer as consumer of the image, while rendering intervention impossible, and this photograph refuses to avert its gaze, the poem’s precision becoming a sort of penance for the speaker’s comfortable distance from pain.

The naked child has drawn her knees up

to her chest, her forehead pressed against

years of parched ground, her forearms

stretched forward and away from either side

of her thinning body, her back to the steadfast bird,

guardian of this warring, drought-stricken plain.

And there is nothing to be done. The speaker knows “the bird can’t be blamed./ This is simply what it knows best,” and all we are capable of is to

want to believe in a wind

such as this one crossing the porch,

that refuses to carry a cry or spread

the scent of finality, and instead braids

strands of warmth through the cool

of evening, between the spaces of outspread

fingers, our hands failed kites,

our lives falling through this luxurious air.

It is a pleasure to watch the way Bargen’s repeated returns to his thematic interests (others include flight versus falling, flight as longing for the sacred) develop the overall structure of Remedies for Vertigo , so that it is a book , not merely a group of poems that happened to find their way between the same end-papers.

Walter Bargen has quietly produced ten collections of highly achieved poetry during the past couple of decades, and Remedies for Vertigo may be his best. Readers who live with it long enough to grow a feel for the echoes between poems and for the music of Bargen’s voice—which underpins the book’s larger architecture—will be more than satisfied.

For those of you who are fortunate, or unfortunate, enough to have a copy of Remedies for Vertigo, you might find this review interesting. No, I do not know this person and I did not pay to have this written. This review appears in www.Thepedestalmagazine.com , issue No. 38.

Prose Poem Sequences

BKMK Press–UMKC, 116 pages, 2003

$14.00 (Illustrated by Mike Sleadd)

Selections:

BEING ITS TIME

In a small Baltic town, on a cold overcast day that could have been yesterday a century ago, and for all practical possibilities will probably be tomorrow a century from now, and whose indeterminancy turned the maypole in the hay-stacked field just east of the last half-timbered houses into a spear stuck in the frozen ground by a falling warrior of Valhalla—here Heidegger slipped beyond his and anyone else’s journal. He abandoned future biographers who might scour the town for street corners where the great thinker stood, so they could ponder what he might have pondered, such as seeing his reflection in the window of the shoe-repair shop. He stepped away from the preponderance of philosophers who would keep turning the pages until they were blank as the coming Arctic snow¬. It was there at the small desk in the inadequately heated third-floor room, which was really an attic he rented under an alias, where each breath hinted of the last, that he first wrote that the only thing worth thinking is the unthinkable.

Heidegger had dipped his stork-white quill into the inkwell and flown into the dark, not knowing if he would ever return. There was elation among those who thought he had given birth to the unknown or, less, that he made the improbable probable. Accident became coincidence, coincidence synchronicity, and synchronicity the fine tuning of the cosmos. Whole tired towns swore off potatoes and turnips, and starved, believing they could live on the light of his thinking. These emaciated towns became known as the first voluntary pogroms. A man bloodied his face trying to run through a wall, but the rumor persisted of his success. Throughout the country large bandages flowered over noses, as if an early sign of spring. Women hanged themselves from ceilings, hoping to get closer to heaven, and had to be cut down. Finely braided rope burns around delicate necks became high fashion. Photographers began keeping records of the soul using glass negatives. To be crowned unthinkable became the rage.

For others the century was a curse. There was the unthinkable factory job, the unthinkable war that led to the next unthinkable war, and the unthinkably cold tenements in the cities. The unthinkable kept looming larger, leading to the unthinkable bomb. And then there’s the unthinkable God enslaved to eternity, and Heidegger’s own unthinkable being thinking in a darkening world.

LOST CREW

Book 6

. . . the victim and the executioner.

–Baudelaire

The snow begins to melt, and the yellowed grass spikes up from a poorly seeded lawn left half-finished by a construction crew. He sits in a parked car thinking it looks more like clumps of hair left after chemotherapy or radiation, or whatever it is we choose to do to ourselves after we discover that it’s too late, that it’s been done to us.

This isn’t to blame the victim, we all are victims, and not to diminish the executioners either. They hone blades on their own histories, which is also us. From that first eye-opening moment when our luminous gray irises float on small fat faces, when we see through it all and never see a thing again, when we are nothings with limitations, it’s really the world falling in on us.

The random patterns turn our small hairless heads, if we have the strength, and no matter which way we look there is something falling into our nothingness. If we cry, the liquid lenses just magnify and bring whatever it is closer and upside down in the sliding of our salts. We can’t stop the faces from falling down on us: mother, father, siblings, all the strangers that we later search for, flipping through photo albums, phone books, skimming rush hour crowds on city streets, for the rest of our and their lives, believing there’s a chance we can resolve, perhaps understand that one haunting glimpse from so long ago.

In jaundiced lighting of airport terminals, slouching in stiff chairs, we exhaust ourselves half-recognizing each traveler who passes, the concourse filling with half-recollections, thinking this is how they might look twenty, thirty years later, leading a child or carrying a briefcase, walking arm-in-arm with someone we should know, smiling, waving goodbye, hello. We must restrain ourselves from running up to them, saying, “Aren’t you . . . ? Did you know . . . ? Do you live in . . . ? Did you go to school at. . . ?” Restrain ourselves if only to save our reputations and conceal the desperation, knowing we carry this same burden around with us, that we are only half recognizable to anyone else, half of what someone’s searching for, yet we will wear out our knees trying to make up the difference with the half of us that hasn’t drifted beyond our reach, the half that someone else is sure they know, though we have never met them before.

He sits in a parked car staring at the snow’s conflagration, the glare off the remaining sooty patches, and flips through the pages of Homer that he has promised himself to read. He catches a movement out the corner of his eye, and wonders if it’s someone who thinks he knows him. Quickly he turns his head, glances in the rearview mirror, but there’s only the smoldering shadow of Troy.

Reviews:

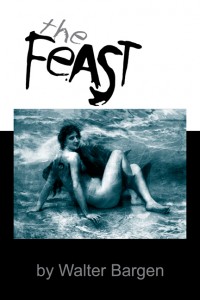

CHEW ON THIS AND IT’S NOT A STICK OF TRIDENT:

A REVIEW OF WALTER BARGEN’S THE FEAST

If one is craving food for thought, The Feast is the book on which to indulge, and the poems within exhibit the type of self-indulgence that poetry should: exploring the link between personal imagination and the means through which it translates into the linguistic: how thought becomes word. These prose-poems sequences display the energy of axons firing signals from receptor to receptor, and the quick-paced language that results could only manifest when there is no insistence on line. The form decodes these impulses into articulate strings of words that resonate in the pit of one’s stomach. Readers find themselves in a state of déja vu when immersed in these poems because, although the content is the product of one man’s imaginative experience, the language springs from an innate common medium: the language of thought itself (mentalese).

Bargen seems to pull this off by bombarding the reader with a seeming overload of sensory input. But this is precisely how human beings take in information and how the mind/imagination turns it over with itself. Thoughts shift more rapidly than a cosmic clock. “Exhausted Spectrum” is a good example of this. (Even the poem’s title indicates its intent.) The poem moves in and out of its character’s (Jonah’s) consciousness. Jonah ponders his existence, his humanity, his mortality while the poem’s speaker expounds the character’s wounds. The poem travels between the internal and the external: “Down the street there are friends missing . . . and then back to Jonah’s more pressing concerns “The wounds shimmer, the preened feathers of plucked angels.” Not only can readers identify with Jonah’s human experience, but seem to be of him as well because the language mimics thought. Think of Einstein when he first imagined himself riding beams of light. This is not to say that the poems are difficult to follow„Ÿone simply enjoys the word and image play and allows him/herself to be transported to wherever the poems go. When in the presence of nerve impulses firing at lightning-like speed, what else can one do but become immersed in the genius that language is in translating thought.

However, because language is largely an arbitrary system, the translation process produces a loss of purity. It is indeed when humans articulate their perceptions that all went awry; it is, perhaps when we fell from grace because we had a tool with which to question. It isn’t so much that we were innocent from the get go and that language corrupted us: it is that we were able to express whatever dark curves our thoughts sometimes strayed to. Anything that one can imagine is possible, but it is words that make imagination imminent. Bargen expresses this throughout the book but perhaps best in the poem “The Blue and Black Book.” The poem begins:

In a small unnamed Baltic town, close enough to the sea that one can smell the salt crystallizing in the tidal winds sighing inland each day during the summer months, there was to be found„Ÿtaking a deep breath that expands the chest into a false sense of belonging to something eternal„Ÿa true hint of a beginning.

That opening sentence demonstrates the type of seeming digressionary overload of the sensory mentioned earlier, but it also served in communicating what I see as the books main agenda: the thought/language continuum and its effect on the human psyche. The poem, in the second stanza, continues:

On the crowded walls of his small room hung souls frowning with the look of those drowning in deep thoughts. He sat troubled. If in the beginning was the Word„Ÿa clearly spoken, though assuredly and not easily understood one„Ÿthen innocence never existed, since every true word is married to its false compliment. So, if the in the beginning was the Word, then also, in the beginning was not the Word. As soon as something was heard, it was not heard.

If one has ever paid attention to what one is thinking, in any significant way, one will recognize that this is the way thoughts fleet. And perhaps this nature of thought„Ÿthe speed, as well as the conflict between poles is what causes the inherent conflicts within human beings. But it is also what makes us beautiful. When language is true as it is in these poems, we are redeemed.

Jen Reid

REDACTIONS 4/5

p 66-67